The Allure of AI-Powered Test Coverage

Achieving high test coverage can be a slog. Manually writing tests for every nook and cranny is time-consuming and tedious. It often requires ugly and unintuitive boilerplate to create all the necessary mocks, stubs, fakes, and so on.

It is tempting to turn to LLMs to address this problem. They are very good at writing boilerplate and have infinite patience for tedious tasks. The workflow seems straightforward: run tests, generate a coverage report, identify the gaps you care about, feed the report to an LLM, ask it to fill the relevant gaps, review the results, and edit them as needed.

However, this approach hits a snag: LLMs are not great at interpreting standard test coverage reports. These reports typically provide line numbers indicating uncovered code. However, LLMs often misidentify these lines. They will guess a line in the right vicinity and then will often tell you that the line is covered and suggest that the coverage tool is not working properly.

This behavior is not entirely surprising. LLMs can struggle with precise counting tasks (e.g., “How many ‘r’s in ’strawberry’?”). They also sometimes refer to suggested edits from earlier in a conversation that might not match the current state of the file. My experience with Gemini 2.5 via Cursor shows that providing a line number isn’t a reliable way to direct the LLM to the specific code in question.

For instance, in one of my development sessions, a coverage report indicated lines 456-457 of a file were untested. Those lines contained some error handling, but the LLM instead latched onto a nearby pragma: no cover comment and an adjacent blank line and tried to tell me that the coverage tool was misbehaving. I had to correct it repeatedly and eventually feed it the exact code that was uncovered.

Bridging the Gap: A Better Coverage Report

The solution lies in enhancing our coverage reports. The pytest-cov extension for pytest doesn’t offer a built-in way to directly output the content of missing lines to the terminal. It can show line numbers or generate annotated files, but for LLM interaction, we need a more direct approach: a list of the actual code lines that are missing coverage, annotated with their original line numbers to help the LLM (and us) locate them.

Here is a bash script that addresses this problem. It runs pytest with coverage, and if the tests pass, it then processes the coverage data to output the specific lines of code that were not executed, along with their file names and line numbers.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -uo pipefail

source .env

#######################################################################################

# 1. Run the tests with coverage and capture exit status

#######################################################################################

uv run pytest \

--cov=. \

--cov-report=annotate

test_status=$?

#######################################################################################

# 2. Generate temp coverage files and show missing-line details if tests passed

#######################################################################################

if [ $test_status -eq 0 ] && [ -f .coverage ]; then

echo -e "\nMissing-line details:"

grep -R --line-number '^!' --include='*.py,cover' . \

| awk -F: '{sub(/,cover$/,"",$1); gsub(/^!/,"",$3); print $1 ":" $2 ": " $3}'

fi

#######################################################################################

# 3. Enforce coverage threshold

#######################################################################################

threshold=100

if [ $test_status -eq 0 ]; then

uv run coverage report --fail-under=$threshold

cov_status=$?

else

cov_status=0

fi

#######################################################################################

# 4. Always clean up temp files

#######################################################################################

find . -name '*.py,cover' -delete

rm -f .coverage

#######################################################################################

# 5. Propagate the correct exit code

#######################################################################################

if [ $test_status -ne 0 ]; then

exit $test_status # tests failed

fi

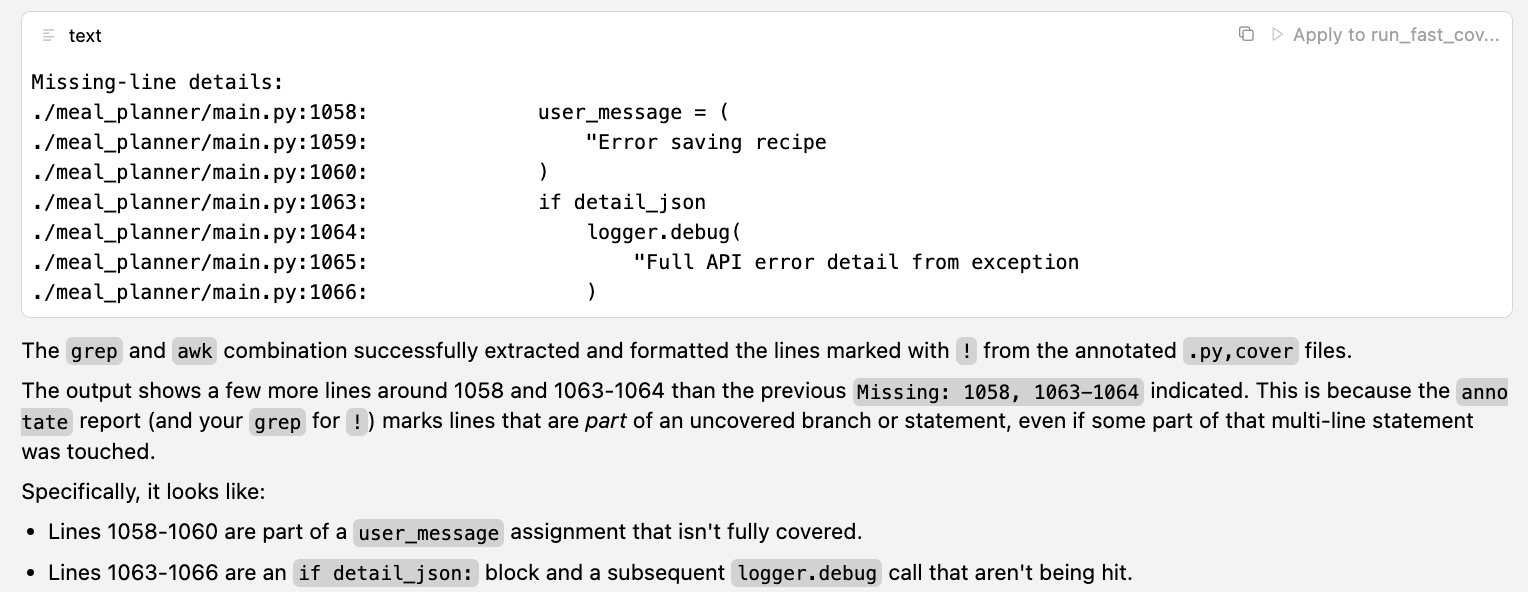

exit $cov_status # 0 if good, 2 if coverage too lowLLMs have a much easier time identifying the correct lines to address based on the output of this script:

Conclusion: A Tool, Not a Panacea

It is important to keep in mind that test coverage is just a heuristic. Even 100% test coverage is not sufficient to guarantee that code is well-tested, nor is it necessary. It might be more trouble than it is worth, even with LLMs, especially for code that is changing rapidly.

That said, checking for coverage gaps can be a useful way to find code that is not as well-tested as it should be. LLMs can make addressing those gaps easier than ever, especially if we use something like the script above to give them the relevant information in a format that they can work with effectively.