This post is part of a series on evaluating classification models:

- Part 1: Weighing False Positives Against False Negatives explains why we need systematic ways to evaluate classification models.

- Part 2: The Sufficiency of Precision and Recall explains why precision and recall are sufficient for evaluating classification models in typical cases.

- Part 3: \(F_\beta\) and Other Weighted Pythagorean Means of Precision and Recall explains what patterns of preferences are encoded by the Pythagorean means of precision and recall. This class of metrics includes the popular \(F_\beta\) family, among others.

- Part 4: Weighted Power Means of Precision and Recall generalizes beyond the Pythagorean means to the broader class of weighted power means of precision and recall.

This series differs from other discussions of evaluation metrics for classification models in that it aims to provide a systematic perspective. Rather than providing a laundry list of individual metrics, it situates those metrics within a fairly comprehensive family and explains how you can choose a member of that family that is appropriate for your use case.

The previous post describes the weighted “Pythagorean” (arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic) means of precision and recall. The arithmetic mean with weight \(\gamma\) says that you are willing to trade one unit of precision for \(\gamma\) or more units of recall, regardless of the current precision and recall. It is appropriate in situations such as medical testing where an individual false positive or false negative is basically unaffected by the total number of false positives and false negatives. For a harmonic mean, by contrast, the number of points of units you require in exchange for one unit of precision depends on the current precision and recall. The same is true for a geometric mean, but to a smaller degree. As a result, a geometric or harmonic mean may be appropriate in settings such as information retrieval where the cost of a false positive or false negative depends on the “big picture” of the model’s outputs.

This post discusses the full class of weighted power means of precision and recall, which includes the Pythagorean means as special cases. It may be overkill for practical purposes: an appropriately weighted arithmetic or harmonic mean is good enough for most problems, and using anything else will probably confuse your collaborators. However, it will give you a stronger handle on how the Pythagorean means work as well as additional options for handling unusual situations.

Weighted Power Means

The weighted arithmetic, geometric, and harmonic means are all instances of the class of weighted power means (defining the Weighted Power Mean with \(\phi=0\) to be the limit of the class as \(\phi\) approaches 0):

\[ \text{Weighted Power Mean}(\gamma, \phi): \left(\frac{1}{1 + \gamma} \left(\gamma P^\phi + R^\phi \right)\right)^{1/\phi} \]

\(\phi=1\) yields the weighted arithmetic mean:

\[ \text{Weighted Arithmetic Mean}(\gamma, \phi=1): \left(\frac{1}{1 + \gamma} \left(\gamma P + R \right)\right) \]

\(\phi=-1\) yields the weighted harmonic mean (the inverse of the arithmetic mean of the inverses):

\[ \text{Weighted Harmonic Mean}(\gamma, \phi=-1): \left(\frac{1}{1 + \gamma} \left(\gamma P^{-1} + R^{-1} \right)\right)^{-1} \]

The weighted geometric mean turns out to be the limit of this expression as \(\phi\) approaches 0:

\[ \begin{align*} \text{Weighted Geometric Mean}(\gamma, \phi\to0) &= \lim_{\phi\to0} \left(\frac{1}{1 + \gamma} \left(\gamma P^\phi + R^\phi \right)\right)^{1/\phi} \\ &= \exp \left(\frac{1}{1 + \gamma} \left(\gamma \ln P + \ln R \right)\right) \\ &= (P^\gamma R)^{1/(1+\gamma)} \end{align*} \]

We saw in the previous post that the weighted arithmetic mean has level curves that are straight, indicating that you would trade one unit of precision for \(\gamma\) or more units of recall regardless of the current values for precision and recall. I recommend reviewing that post now if it is not fresh in your mind.

By contrast, the geometric and harmonic means have level curves that curve upward, indicating that you care more about recall relative to precision for instance when recall is \(.1\) than when recall is \(.9\), holding precision fixed.

The more general class of weighted power means can have level curves that curve in either direction and to whatever degree we like. As you take \(\phi\) toward -infinity in the plot above, the level curves approach two straight lines meeting at a right angle. That metric cares about only whichever of precision and recall is lagging behind. With the weight parameter \(\gamma=1\), it is just the minimum of precision and recall.

Here are the level curves for the weighted power means as a function of \(\gamma\) with \(\phi=-2\).

When you set \(\phi>1\), the level curves curve downward, indicating that you care about increasing precision more than we care about increasing recall when precision is high compared to recall, and vice versa. I am not aware of any real classification problems where this behavior seems appropriate, but if such a problem were to arise then we would be able to handle it with a weighted power mean. With \(\gamma=1\), the weighted power mean converges to the maximum of precision and recall as \(\phi\) goes to infinity.

Here are the level curves for the weighted power means as a function of \(\gamma\) with \(\phi=2\).

A Better Parameterization

Weighted power means of precision and recall form a useful class of metrics for evaluating classification models. However, the standard way of parameterizing that class is not ideal for our purposes. The plot below shows the level curves for the weighted power means as a function of \(\phi\) with \(\gamma=3\). Observe that changing \(\phi\) affects not only the curvature of the level curves around the black line, but also the location of the black line.

Ideally, we would have separate control over those two aspects of our metric. One parameter would affect only the slope of the black line, which represents the overall importance of recall relative to precision as the recall/precision ratio at which we care about them equally. The other would affect only the curvature of the level curves, which represents how our concern for recall relative to precision changes as we move away from that break-even recall/precision ratio.

The key is to replace the weight parameter \(\gamma\) with \(\beta=\gamma^{1/(\phi+1)}\). (We made special cases of this substitution for the harmonic and geometric means in the previous post.) While we are at it, I would like to replace the curvature parameter \(\phi\) with \(\rho=\phi+1\) so that the level curves curve upward for negative \(\rho\) and downward for positive \(\rho\), with \(\rho=0\) (the arithmetic mean) as a neutral point.

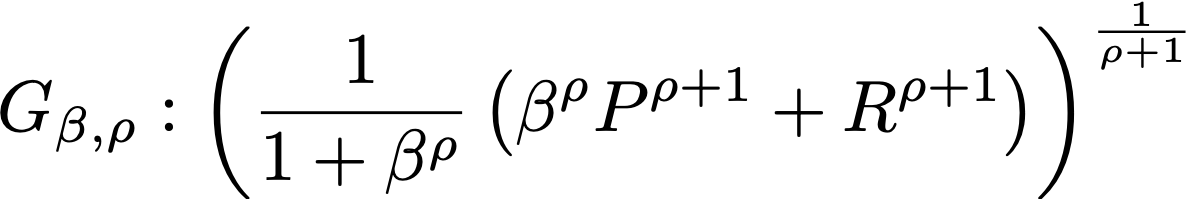

Here is the resulting family of metrics. For lack of a better name I will call it \(G_{\beta,\rho}\) because it generalizes \(F_\beta\):

\[ G_{\beta,\rho} = \left(\frac{1}{1 + \beta^\rho} \left(\beta^\rho P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right)\right)^{\frac{1}{\rho+1}} \]

In the case \(\rho=0\), this expression reduces to the simple arithmetic mean \(1/2(P+R)\), and the weighting is lost. For generality, I will stipulate an expression for that special case that preserves the weighting:

\[ G_{\beta,\rho=0} = \frac{1}{1 + \beta} \left(\beta P + R \right) \]

The expression approaches the geometric mean as \(\rho\) approaches -1, so I will stipulate that \(G_{\beta,\rho}\) just is the geometric mean in that case:

\[ G_{\beta,\rho=-1} = \left(P R^\beta\right)^{\frac{1}{1+\beta}} \]

The standard \(F_\beta\) score (i.e., the harmonic mean) corresponds to \(G_{\beta,\rho}\) with \(\rho=-2\).

Observe that in the plots below, changing \(\beta\) affects only the location of the black line (i.e., the value of the recall/precision ratio where we are equally concerned about improvements in one or the other). This first plot uses \(\rho=-3\), so that the level curves curve upward more strongly than those of the harmonic mean (\(\rho=-2\)). Notice that the curvature of the level curves stays the same as you vary \(\beta\).

The next plot uses \(\rho=3\), so that the level curves curve downward. Again, varying \(\beta\) changes the location of the black line but not the curvature of the level curves around that line.

On the other hand, changing \(\rho\) affects only the curvature of the level curves around the black line (i.e., how our concern for recall versus precision shifts as their ratio departs from that value), and not the location of the black line. The plot below illustrates this point for \(\beta=2\).

We have made the family of weighted power means orthogonal with respect to (1) how much we care about recall versus precision overall (the location of the black line) and (2) how that concern shifts with recall and precision (the curvature of the level curves around the black line). See the appendices at the bottom of this post for further details.

Conclusion

\(G_{\beta,\rho}\) is a new family of evaluation metrics for classification models. The \(\beta\) parameter expresses how much you care about recall versus precision overall, just like \(\beta\) in the popular \(F_\beta\) family. More precisely, it specifies the ratio of recall to precision where you would be equally happy with a one-unit increase in precision or a one-unit increase in recall (in the limit as the size of the unit goes to 0).

The \(\rho\) parameter expresses how your concern about recall versus precision shifts as the recall/precision ratio moves away from that special \(\beta\) value.

For the weighted arithmetic mean (\(\rho=0\)), your concern for recall versus precision does not shift at all: you would trade one unit of precision for \(\beta\) units of recall regardless of the current values of precision and recall. This subclass of metrics is appropriate for settings such as medical testing where the expected cost of a single false positive or false negative is more or less fixed regardless of the total number of false positives and false negatives.

\(\rho<0\), by contrast, expresses that you are more concerned about recall than precision when the ratio of recall to precision is less than \(\beta\) and more concerned about precision when it is greater than \(\beta\). The smaller the value for \(\rho\), the more your concern shifts toward whichever of precision and recall would need to increase to bring their ratio back toward \(\beta\). This sort of metric seems appropriate for settings such as information retrieval where the cost of a single false positive or a false negative depends on its contribution to the overall impression created by a set of predictions.

\(F_\beta\) has this general character, but it fixes the “curvature” parameter \(\rho\) to -2, which may not be appropriate for all scenarios. The more comprehensive \(G_{\beta,\rho}\) family allows us to fine-tune an evaluation metric for cases in which our concern for recall relative to precision shifts with their ratio more or less strongly than \(F_\beta\) assumes.

Epilogue: What Else Is There?

\(G_{\beta,\rho}\) has a lot of flexibility, but it is not fully general. In the special case of the weighted arithmetic mean (\(\rho=0\)), it says that you are willing to trade one unit of precision for \(\beta\) units of recall regardless of the current precision and recall. In other cases, it says that there is a ratio \(\beta\) of recall to precision where you would be willing to trade one unit of precision for one unit increase of recall. If your preferences don’t match either of those patterns, then no member of \(G_{\beta,\rho}\) represents them.

We can still say something about what kinds of measures might be appropriate in such a case: van Rijsbergen showed that under quite general conditions, one’s preferences over models can be represented by a sum of a function of recall and a function of precision (Information Retrieval, p. 132), in the sense that this function will give a higher score to Model A than to Model B if and only if one prefers Model A to Model B. Moreover, this measure is unique up to rescaling by addition and multiplication by constants. This result signifies that any reasonable metric for a binary classification model can be decomposed into the sum of a function that depends only on recall and a function that depends only on precision.

Appendix: Technical Details

Demonstration That \(\beta\) Does Its Job

I have said that \(\beta\) specifies the ratio of recall to precision where you would be equally happy with a one-unit increase in precision or a one-unit increase in precision. Let’s demonstrate this result. Stated precisely, it says that the partial derivatives of \(G_{\beta,\rho}\) with respect to \(R\) and \(P\) are equal when \(R/P=\beta\).

\[ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial}{\partial R} \left[ \left( \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right)^{\frac{1}{\rho+1}} \right] &= \frac{\partial}{\partial P} \left[ \left( \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right)^{\frac{1}{\rho+1}} \right] \\ \frac{1}{\rho+1} \left[ \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right]^{\frac{-\rho}{\rho+1}} \left(\frac{\rho+1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \right) R^{\rho} &= \frac{1}{\rho+1} \left[ \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right]^{\frac{-\rho}{\rho+1}} \left( \frac{\rho+1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \right) \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho} \\ R^{\rho} &= \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho} \\ \beta &= \frac{R}{P} \end{align*} \]

This derivation works unless \(\rho=0\). In that case we are dealing with a weighted arithmetic mean, so there are no values of \(R\) and \(P\) at which we are willing to trade one unit of recall for one unit of precision unless \(\beta=1\), and in that case we are willing to do so at every value of \(R\) and \(P\).

Demonstration That \(\rho\) Does Its Job

The “curvature” parameter \(\rho\) characterizes how our concern for recall relative to precision changes as we move away from the neutral line \(R/P=\beta\). More precisely, it characterizes the rate of change of the slope of the tangent line to a level curve \(R/P=\beta\) along the direction of that tangent line.

The slope of the tangent line to a level curve of the weighted power mean is given by the ratio of the partial derivative of the weighted power mean with respect to recall to its partial derivative with respect to precision. Call this quantity \(S\). Then we have

\[ \begin{align*} S &= -\frac{\frac{\partial}{\partial R} \left[ \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right]^{\frac{1}{\rho+1}}} {\frac{\partial}{\partial P} \left[ \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right]^{\frac{1}{\rho+1}}} \\ &= -\frac{\frac{1}{\rho+1} \left[ \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right]^{\frac{-\rho}{\rho+1}} \frac{\rho+1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} R^{\rho} } {\frac{1}{\rho+1} \left[ \frac{1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \left( \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho+1} + R^{\rho+1} \right) \right]^{\frac{-\rho}{\rho+1}} \frac{\rho+1}{1 + \beta^{\rho}} \beta^{\rho} P^{\rho}} \\ &= -\left( \frac{R}{\beta P} \right)^{\rho} \end{align*} \]

We want to characterize how the slope \(S\) of the tangent line to the level curve of the metric changes along that tangent line, so we need to evaluate the partial derivative of \(S\) with respect to \(t=R-P\). By the chain rule,

\[ \begin{align*} \frac{\partial S}{\partial t} &= \frac{\partial S}{\partial R} \frac{\partial R}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial S}{\partial P} \frac{\partial P}{\partial t} \\ &= \frac{\partial}{\partial R} \left[ -\left( \frac{R}{\beta P} \right)^{\rho} \right] \frac{\partial}{\partial t} (t + P) + \frac{\partial}{\partial P} \left[ -\left( \frac{R}{\beta P} \right)^{\rho} \right] \frac{\partial}{\partial t} (R - t) \\ &= -\rho \left( \frac{R}{\beta P} \right)^{\rho} R^{-1} - \rho \left( \frac{R}{\beta P} \right)^{\rho} P^{-1} \\ &= -\rho \left( \frac{R}{\beta P} \right)^{\rho} \left( R^{-1} + P^{-1} \right) \end{align*} \]

So

\[ \left. \frac{\partial S}{\partial t} \right|_{\beta = \frac{R}{P}} = -\rho \left( R^{-1} + P^{-1} \right) \]

Thus, for a given \(R\) and \(P\) along the line \(\beta=R/P\), the curvature of the level curve along the direction of its tangent line is proportional to \(\rho\).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nicole Carlson, Morgan Cundiff, and the rest of the ShopRunner data science team for comments on earlier versions of this material.

Originally published at medium.com